Address Sequencing in Microprogrammed Control Units

Microinstructions are stored in control memory in groups, with each group specifying a routine. Each computer instruction has its own microprogram routine in control memory to generate the microoperations that execute the instruction. The hardware that controls the address sequencing of the control memory must be capable of sequencing the microinstructions within a routine and branching from one routine to another.

To understand the address sequencing in a microprogram control unit, let us detail the steps that the control unit undergoes during the execution of a single computer instruction.

Initial Address Loading

When power is turned on, an initial address is loaded into the control address register (CAR). This address typically points to the first microinstruction that activates the instruction fetch routine. The fetch routine is sequenced by incrementing the CAR through its microinstructions. At the end of the fetch routine, the instruction is loaded into the instruction register of the computer.

Effective Address Computation

Next, the control memory executes the routine that determines the effective address of the operand. A machine instruction may have bits specifying various addressing modes, such as indirect addressing and index registers. The effective address computation routine in control memory is reached through a branch microinstruction, conditioned on the status of the mode bits of the instruction. When this routine completes, the operand address is available in the memory address register.

Instruction Execution

The next step is to generate the microoperations that execute the fetched instruction. The microoperation steps depend on the opcode part of the instruction. Each instruction has a specific microprogram routine stored in a particular location in control memory. Transforming the instruction code bits to a control memory address is called the mapping process. This mapping procedure transforms the instruction code into a control memory address.

Once the routine is reached, the microinstructions that execute the instruction may be sequenced by incrementing the CAR. Sometimes, the sequence of microoperations depends on the values of certain status bits in processor registers. Microprograms that employ subroutines will require an external register for storing the return address, as ROM has no writing capability.

Returning to Fetch Routine

When the instruction execution is complete, control returns to the fetch routine via an unconditional branch microinstruction to the first address of the fetch routine.

Address Sequencing Capabilities

The address sequencing capabilities required in control memory are:

- Incrementing the control address register.

- Unconditional or conditional branching, depending on status bit conditions.

- A mapping process from instruction bits to a control memory address.

- Subroutine call and return facilities.

Address Selection

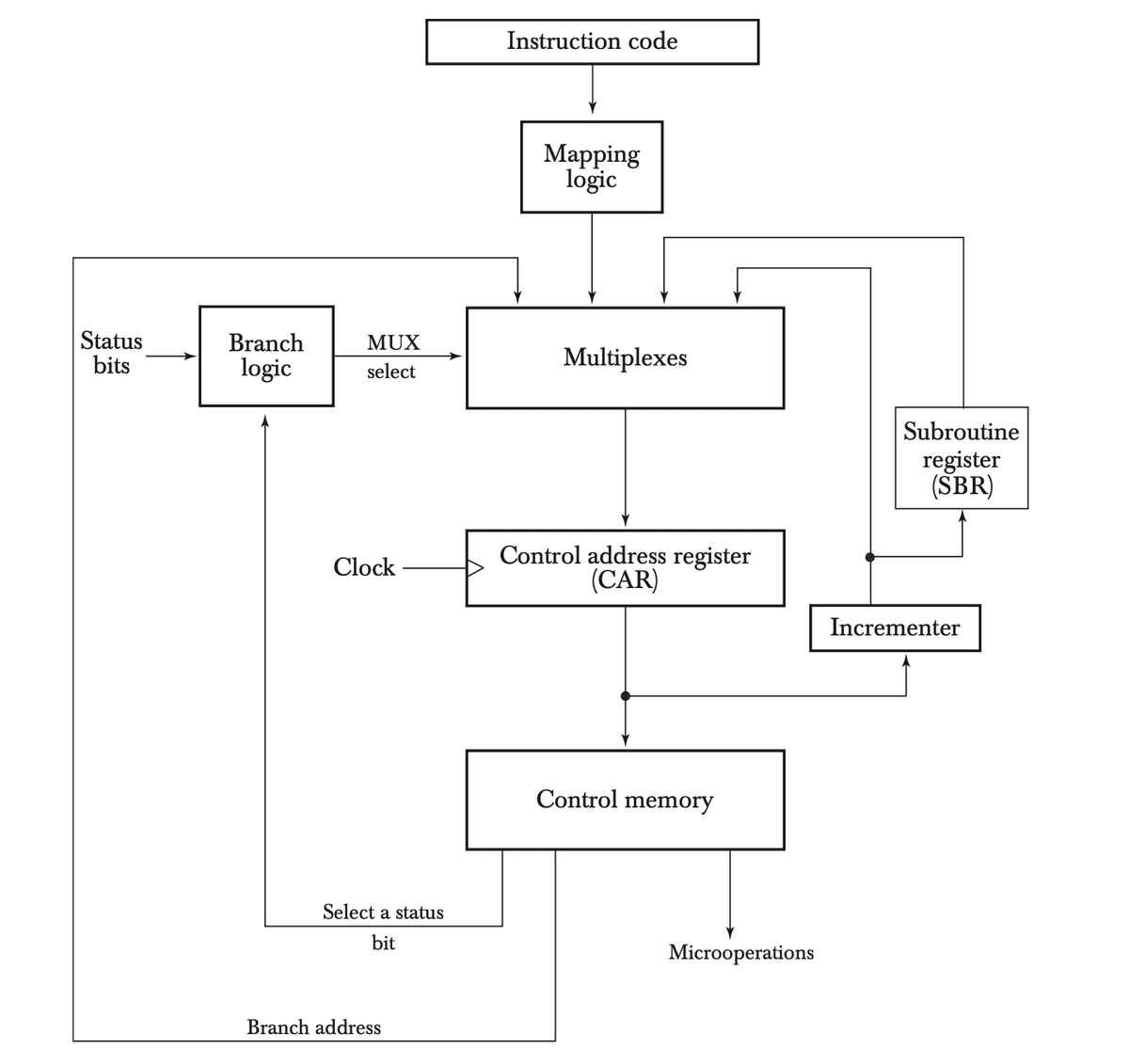

A block diagram of control memory and its associated hardware shows four different paths for the CAR to receive the address:

- Incrementing: The incrementer increments the CAR content by one to select the next microinstruction in sequence.

- Branching: Branching is achieved by specifying the branch address in one of the microinstruction fields.

- Conditional Branching: Part of the microinstruction selects a specific status bit to determine its condition.

- External Address: Transferred via a mapping logic circuit.

- Subroutine Return: The return address for a subroutine is stored in a special register, used when the microprogram returns from the subroutine.

Conditional Branching

The branch logic provides decision-making capabilities. Status conditions, special bits in the system, provide information such as the carry-out of an adder, the sign bit of a number, mode bits of an instruction, and I/O status conditions. These bits can be tested, and actions are initiated based on their condition (1 or 0). The status bits, together with the field in the microinstruction that specifies a branch address, control the conditional branch decisions.

The branch logic hardware may be implemented in various ways. The simplest method is to test the specified condition and branch to the indicated address if the condition is met; otherwise, the CAR is incremented. This can be implemented with a multiplexer. For example, with eight status bit conditions, three bits in the microinstruction specify one of eight conditions. These three bits are the selection variables for the multiplexer. A 1 output from the multiplexer generates a control signal to transfer the branch address from the microinstruction to the CAR, while a 0 output causes the CAR to increment.

An unconditional branch microinstruction can be implemented by loading the branch address from control memory into the CAR. This can be done by fixing the value of one status bit at the multiplexer input, ensuring it is always 1. A reference to this bit by the status bit select lines from control memory causes the branch address to load into the CAR unconditionally.

Mapping of Instruction

A special branch exists when a microinstruction specifies a branch to the first word in control memory where a microprogram routine for an instruction is located. The status bits for this branch are the bits in the opcode part of the instruction. For example, a computer with a 4-bit opcode (allowing up to 16 distinct instructions) and 128 words in control memory (requiring a 7-bit address) uses a simple mapping process. This involves placing a 0 in the most significant bit of the address, transferring the four opcode bits, and clearing the two least significant bits of the CAR. Each instruction thus has a microprogram routine with a capacity of four microinstructions. If more than four microinstructions are needed, addresses from 1000000 to 1111111 can be used. If fewer microinstructions are needed, the unused memory locations are available for other routines.

This concept can be extended to a more general mapping rule using a ROM to specify the mapping function. The instruction bits specify the address of a mapping ROM, whose contents give the bits for the CAR. This method allows the microprogram routine for the instruction to be placed anywhere in control memory, providing flexibility for adding instructions.

Subroutines

Subroutines are programs used by other routines to accomplish a specific task. A subroutine can be called from any point within the main microprogram. Many microprograms contain identical sections of code, which can be saved by using subroutines. For instance, the sequence of microoperations needed to compute the effective address of the operand for an instruction is common to all memory reference instructions and can be a subroutine.

Microprograms using subroutines must store the return address during a subroutine call and restore it during a return. This is done by placing the incremented CAR output into a subroutine register and branching to the subroutine's start. The subroutine register then becomes the source for transferring the address for returning to the main routine. A LIFO (last-in, first-out) stack is the best way to structure a register file storing addresses for subroutines. This stack mechanism is detailed further in subsequent sections.